When I was in third grade (or maybe it was second), I wrote a poem about sunset, and rest. I did it in number 2 pencil on a sheet of wide-ruled paper torn out of a 78-cent spiral notebook. I illustrated the edges, with an angry sun and an optimistic moon, and my best effort at a seagull. I can remember this in such clear detail, because I’ve still got that page. It’s creased with folds, and the pencil’s faded, but I’ve still got it, tucked away somewhere. The meter is awful.

In the summer of my twelfth year, when I came home from a week at Grandma’s to learn my dad had interviewed for and accepted a job three hundred miles away, I wrote a deeply heartfelt three-stanza poem to all the friends I’d be leaving behind. It took me three weeks to get it right, it was deeply maudlin, and in the end it proved to be packed with promises that I didn’t actually keep. I was just a kid…what did I know?

In high school, I decided to become a poet entirely on the sound principle that “chicks dig poems.” Shallow as it was, it wasn’t wrong. I can’t say with confidence that I landed any girlfriends entirely from the poetry, but I know I avoided some disasters (and saved a pretty penny on Valentine’s and Mother’s Day gifts) with some well-placed rhymes. I’ve still got a bunch of them — literally hundreds, all the ones I ever wrote to the girl who ended up becoming my wife — and I still read through them from time to time. I’m proud to say they make me smile almost as often as they make me wince.

Growing Up

Somewhere in there, though…somewhere in that last year of high school and first year of college, I started taking myself seriously. Quantity plummeted, and quality started creeping in. I started reading the work of other poets, and paying attention. I started learning why people liked Eliot, and Post, and cummings, even though I didn’t. (And, in the process, I sort of learned to like them, too.) I started studying syllabic meter, standard rhyme schemes, and stanza structures.

I wasn’t writing for chicks anymore, either. I wasn’t writing for anyone, really. I wrote my dissatisfaction with the faith of my fathers. I wrote my frustration with strict naturalists, and my pity for existentialists, and my love for the creator/god/storyteller. It was intensely personal stuff — totally unpublishable — and when I graduated from college, I pretty much left that behind me.

Except…I didn’t. I carried it with me to my blogging. I brought it to my short stories, and caught myself weaving it into my novels. I spent four years really trying to become a poet, and in the process I made myself a better writer for the rest of my life.

The Sound of Your Words

There’s several factors in that claim, some of them abstract and lovely, some of them grungy and technical, and some of them quietly practical. The best example of that last is reading my stuff aloud.

Every writing teacher will tell you to read your work aloud, before you consider it done. I have. Stephen King did. My creative writing teacher in college did, and so did three or four of my teachers in high school. It’s great advice…but it’s too much work. Everyone knows they should, but no one follows through on it.

Well, no one but the poets. Poetry, far more than prose, is the visual expression of spoken words. All language captures spoken ideas, but poetry lifts up the words, poetry traps the very expression itself, wrestles it into submission, and then puts it on display for all to see. Much of the beauty of poetry is in its demonstration of the way people speak, even more than in the thing the poem is actually saying.

Because of that, there’s no way to get a poem right without speaking it. Poets learn early to test their words against the ear, as well as the eye, and in the process they develop the habits that every writer needs to have. They also get better and better at recognizing the shapes of sounds — they develop the instincts to create beautiful-sounding phrases before they read them out loud, and they learn to recognize the bits that aren’t going to sound right, just by sight.

Of course, it helps that poets are working in smaller chunks. It’s a lot easier to make time to read a page out loud than it is to croak through eighty thousand words.

Try, Try Again

That’s one of the real benefits of writing poetry, though: high turnover. You can start a project, devote yourself whole-heartedly to it, and still be done over the weekend. As I said, I wrote hundreds of poems in high school, and dozens in college. In that same span, I wrote two novels. That means, in terms of practicing storytelling, I wrote exactly two introductions, and two conclusions. It’s hard to make huge improvement in a skill with so few repetitions.

Poetry offers a different skillset, but it’s still written communication. It still requires a negotiated connection, and a satisfying ending. I dove into every poem with the understanding that I had to convey my setting, my characters, my scene, in just a handful of words.

You can get that with short stories, and certainly with blog posts — it’s absolutely part of the reason I keep insisting you should have a blog! — but there’s a special magic to poetry.

Words Come Alive

What’s the magic? Love of language. Storytellers often talk about the magical moment when a character comes alive and starts dictating plot. I’m completely certain I’ll talk about it here. It depends a little bit on your writing style, apparently, but most writers experience it at some time — a character you’re writing starts responding to his environment, starts saying things in dialogue you’d never imagined, and starts taking actions you couldn’t possibly have predicted. It’s powerful. It makes incredibly compelling stories, and it’s one of the moments character-driven storytellers live for.

Poetry’s got something similar, but it’s not the characters. It’s the words. The language itself comes alive, and it’s mesmerizing. Not only that…you learn how to do it. You learn how to find that magical space just at the border between abstract and concrete, between spoken and written, between real and imagined — the place where the magic happens. You learn how to find that place, again and again, and eventually you make it your home.

Poetry becomes part of your language, not just a product of it, and then it’s there, wherever you go. Whatever you write, whether it’s a blog post, or a 1,000-page novel, your language writhes and dances, your words sparkle and shine, and your readers hear the harmony singing behind the story you’re telling them.

It’s not an easy task, I know. Especially if you’re already out of school. But learning poetry will make you a better writer, a better speaker, and (why not?) probably a better person, too.

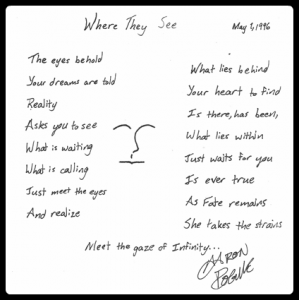

Photo credit Aaron Pogue.

Beautiful post, Aaron. And it makes the comment you left on my post today that much more poignant.

I always tell people to read their work out loud – but we’re usually talking blog posts. I tell them to do to catch editing mistakes, but I know for myself that the reading out loud lets me know if the words sing or not.

And our words deserve a voice…

This is one of my new favorite posts of yours. Now that you mention it, I think I can definitely see the value added to my current writing from my years of writing poetry that mostly embarrasses me now.

Thanks for bringing that to light.

I have gotten in the habit of reading my blog posts out loud, and from the preview screen so I can see it and hear it exactly the way it will be presented. I always – ALWAYS – find lots of improvements to make and errors to correct.

Thanks, Julie! I totally agree. As a Technical Writer, it’s a constant chore to give my words voice, and I know some people who think (in that particular field) it’s a waste of time.

I’ve seen how much more effective a manual or a memo can be (just like any other document) when it expresses and connects, though. For one thing, it gets read (instead of just skimmed), and there’s times when that alone can save lives.

And thanks for backing me up, Carlos. I think most people who have tried writing poetry would say the same thing — and I really hope they will!

Because this post is a message to everyone who hasn’t tried it. Everyone who thinks it’s too complicated or too…I dunno, frilly. You don’t have to share your poetry with anyone. You don’t have to be good. But you need to put in some time really practicing and focusing on those skills, or that musical voice that Julie mentioned will always be missing from your work.

I guess this is a topic I’m a little passionate about. I didn’t realize that….

This is true. I used to write a lot of poetry and that practice made me a better writer.

Surrendering to cadence and rhetorical devices and writing with the express purpose of evoking emotion…is very fine training.

I am self-admittedly one of those chicks who dig guys who write poetry. I used to write it for myself, but when I discovered boys, I shifted from poetry writer to the far less scary role of poetry reader and commenter.

Your post has inspired me that it might be time to give it another try. Any suggestions on how to get started besides digging out those old English texts I stole from my high school?

Hi Aaron,

Ever noticed no one ever paraphrases a poem? The words are so precise–for me that’s what makes poetry magical. As Edward Hirsch says of the craft, “what is being said is always inseparable from the way it is being said.” I’m in love with the lyrical, rhythmic, incantatory language of great poetry and know, without a doubt, that reading it makes my writing better.

Thoughtful post–a pleasure to find your blog.

Woohoo! I got a comment from Kelly Diels. I’m now half as cool as Carlos!

I love that you used the word “surrender,” too. So much of the power of poetry comes from learning to express yourself clearly within constraints. Once you can do that, free prose is easy.

Now…how to get started, Julie? For one, you could do tomorrow’s writing exercise! Spoiler alert: it’s a sonnet. Should be fun.

In general, I’d say for the best practice (as opposed to, say, artistic self-expression), you should absolutely focus on strongly structured poems (sonnets, haikus, ABBA rhyming Iambic quatrains). Free verse can be beautiful, but if you haven’t already mastered structured poetry, free verse won’t move you any closer.

And welcome, Shelly! Ugh, I’ve got to get nested comments going!

I love the point you made, though. I stumble into it from time to time, even with my own stuff. I’ll be discussing some topic near and dear to my heart, and say, “Ooh, I wrote a great poem about that…” and then there’s nowhere to go from there but to read the whole thing (or drop it, of course).

Aaron, how do you respond to people who say they don’t “get” poetry? I have several friends who think my poetry is “neat,” but they say they can’t understand it because poetry in general doesn’t make sense to them. Are they intimidated by the form, or…?

I don’t want this to sound flippant, Courtney, but really this is how I respond to them.

I wrote this article as a direct attempt to address that problem. Obviously, I approached it from a writer’s perspective (and you might just be asking about readers), but the problem you’re describing is one I’m very familiar with.

I think the only way to “get” it is to invest some serious time in it (whether that’s writing or just reading), but that’s a big enough commitment that it requires some serious incentive. Thus my subtitle for this post.

For writers, the incentive is there (and all the comments so far testify to that). For readers (and friends, and family), I really don’t know.

@Aaron: Maybe it really is a ‘practice makes perfect’ sort of thing. If a person is willing to commit time and effort to reading poetry and trying to figure it out, then understanding should follow at some point. I guess that’s a gauge to measure how interested they really are? Not trying to sound petty, just wondering aloud. ;o)

[…] doesn’t matter how great the ideas are, how perfect the rhetorical structure or how clever the turns of phrase. Nothing you write matters until someone reads it, and it only […]

“Poetry, far more than prose, is the visual expression of spoken words.”

I loathe poetry, mostly.

Despite this, Kelly Diels has accused me of being a poet.

I think maybe, I am.

No matter. Whether I like it or not, you have sold me on the value of poetry for making me a better writer. It’s worth it for that alone. I don’t have to like something to learn it, or to benefit from it. Just have to do it. Thanks!